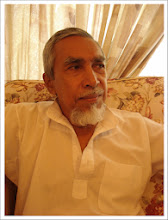

1. I cherish bits and pieces of

my childhood memories of my father. A blurry image of his physical self, his stately

movement and his daily routine still linger in my mind. His personal possessions

especially his books fascinated me as a child. He was a

man of medium build about five foot six I guess although as a small boy I considered

him to be a very big man. He had a pair of tired looking eyes, a rather long

face and receding chin. His grey hair was always trimmed short by an Indian

barber who used to come by regularly. I liked to see him take his usual strides across the

hall especially after lunch and dinner. He took his

meal all by himself with a knife, fork and spoon. In the evening he would usually settle down

in his armchair and smoked a locally made cigar for relaxation.

2. I was nine

when he passed away in 1956. On the night before the funeral, I wept silently beside

his body, which was laid on a bed. I knew then that I’d lost him forever. What

were left were memories and his collection of books, which gave me an early

impression that he was a learned man. The collection included a complete set of

the Encyclopaedia Britanica, volumes

of The Great

War, numerous

volumes of the Journal of Malayan Branch

Royal Asiatic Society and numerous titles of fictions and non-fictions. The

fictions included a number of volumes by Charles Dickens and numerous paperback

and hardcover volumes by Agatha Christie and other authors. There was an

impressive collection of non-fictions as well; two of which that I remember

very well were On the Origin of Species

by Charles Darwin and Relativity: The

Special and General Theory by Albert Einstein, both of which I didn’t

bother to read.

3. Born into a family of merchants in late 19th century George Town, he was destined to make a

name for himself as a civil servant away from his home town. Although he was reportedly inclined to be a school teacher which he

did for several years at his alma mater – fate had diverted him towards a

different line of career. Through sheer determination, hard work and merit he was able to make his

way up in the KCS

after getting his foot in the door working as headmaster of GES, a newly founded English school in Alor

Star. After his tenure in GES he became Senior Auditor

and later held various posts including Registrar of High Court, Acting Sheriff,

Assistant Superintendent Monopolies and Customs, and Assistant to the Legal

Adviser. He was acting 2nd Under Secretary before retiring from the KCS in September 1937.

4. His career in the KCS spanned

over a period of 27 years. The later 14 years were

spent mostly at the Legal Adviser’s office where he and members of a

translation committee collaborated with the LA to accomplish a herculean task

of translating hundreds of enactments, rules and regulations into Malay. He had, to his credit, translated a very large number of enactments all by himself during the time. He was reportedly the

soul of the translation committee and was really the translator of the English version into Malay. He worked expeditiously

at putting every English word in the laws into intelligible Malay.

5. The complete work The Laws

of the State of Kedah (Laws of Kedah),

compiled by G. B. Kellagher,

was first published in 1934 in English and Malay with the Malay version printed

in Jawi. That was about three years away from his retirement. However, the hard work that he and his colleagues put into the Laws of Kedah cuts both ways. Many might

have commended their work as a useful contribution to the State, but many more

who strongly disapproved of colonial jurisprudence might have regarded it

pointless.

The following remarks from a newspaper article might

be worth quoting:

“Altogether the work is a credit to all those concerned in its compilation and publication and supplies a long felt want to any one [sic] who has anything to do with Kedah legally. Previously it was all chaos and one did not know where one stood as to his legal rights in the State.”

6. Being a loyal and hard working

government servant, he had gained valuable experience on the

legal side during his time working as Assistant Legal Adviser. By virtue of that he was recalled to service by the Kedah government

during the Japanese occupation to head the Department of Justice. He held the

post of Legal Adviser and Public Prosecutor for Kedah and Perlis until the end

of the war. He continued to serve through the BMA and retired again in 1946 at

the age of 64. Later he was appointed unofficial member of the Council of State

and the State Executive Council.

7. By reason of his views as expressed in his speeches and letters, I

would deem my father a moderate. He seemed to look up to his fellow unofficial

members and regarded them as a loyal and patriotic lot. According to him they

were a far cry from certain group of people inclined to aggressive

confrontation with the British. He wrote in one of his letters, thus:

“They [the unofficial members] are not of the type of political agitators at the various political organizations who often attack colonialism and expatriate-element of Government to agitate for quick self-government without considering the many drawbacks and obstacles which must be encountered and eliminated by many stages of wise administrative action before the goal of self-government will be fully achieved with full success and satisfaction.”

8. I came across two of his

speeches delivered at the State Council, which seemed newsworthy to local

English newspapers. The first speech delivered in August 1948 concerned his call for the creation

of Mukim Councils

in Kedah. The idea might have been drawn from an

article written by Sir George Maxwell about two months earlier. The article

gave a brief account of the “Parish Councils” in England and suggested that they

might serve as examples for similar Councils in Malay kampongs. In his later article published in August 1958, Maxwell mentioned the speech as

an instance of the public interest in his earlier article. It was nearly two years after my father’s death.

9. The second speech delivered in September 1951

concerned his call for

the improvement of the economic status of the kampong people. In his speech he

criticized Dato’ Onn Ja’afar’s plan to achieve self-government in seven years

as absurd on account of the social, economic, educational and political

position of the Malays were so precarious at the time. His

criticism of Dato’ Onn’s plan seemed to go against the tide, but I hold that it

came about by reason of his down-to-earth attitude. His urge for Government to improve the

economic position of the Malays and to train them in rural industries seemed justifiable.

10. It might not be fair to call him an anglophile or a

colonialist much as it would be wrong to disregard British influence on him. He

was English educated and exposed to English culture in his upbringing in

metropolitan George Town. Later his association with British expatriates during

his times as a young teacher in his home town and much later working with

British officials in Kedah seemed to make him sympathetic towards colonialism.

But it did not necessary mean that he approved of colonialism.

11. Apparently, he did not favour politics along communal

lines. This is obvious in his support for Dato’ Onn Jaafar when he formed the

Independence of Malaya Party. A quote from his letter of support was published

in a newspaper, thus:

“I am at one with you in your wise plan to obtain self-government as early as possible with all the safeguards for our protection and security……”

12. My father was still hard at work in his mid-60s. He reportedly took

up private business after his retirement. I still

recall that he used to don a tasselled tarboosh

to work. It seemed to evince the spirit of the time. He lived in the time of

Islamic reform or modernization, which had its beginning in Egypt and advocated

by ulama like Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh and Muhammad Rashid Redha. In this country similar movement was lead by Sheikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin, Sheikh Muhammad Salim al-Kalali dan

Syed Sheikh bin Ahmad al-Hadi.

13. I still recall numerous

copies of a certain periodical on Islam that propounded modernist ideas and

introducing reformist thought of the time. I am not certain where it was

published; it might be India or Pakistan. It’s a pity that I have also

forgotten what its title was. He also possessed a copy of the holy Qur’an with

English translation and commentary by Abdullah Yusuf Ali. My mother used to keep a miniature Qu’ran locket, a

memento he left her.

14. My father had reportedly been a great teacher

in English education as well as a great civil servant of the best traditions of

the civil service. But what fate had in store for him in his retirement age

might have been phenomenal – the birth of his three children. Prior to my earnest effort to research my

father I knew so little about him on account of our age gap. During my childhood my father was

in his late 60s and was hard of hearing, so conversation hardly ever occurred

between us.

15. As I recall

he was quite indifferent to me and my siblings for one reason or another. But

this did not necessarily mean that he did not care for us. Maybe he had passed

the age of becoming a parent when we were born. My siblings and I were

apparently more like grandchildren to him than natural children. Our

relationship was never meant to reach mutual affection although I had a hidden

fondness for him.

No comments:

Post a Comment